The two works that follow are attempts to foreground the perspectives of the mice, which are at the centre of these experimental ethologies in different forms.

Sketching the perspective of a mouse

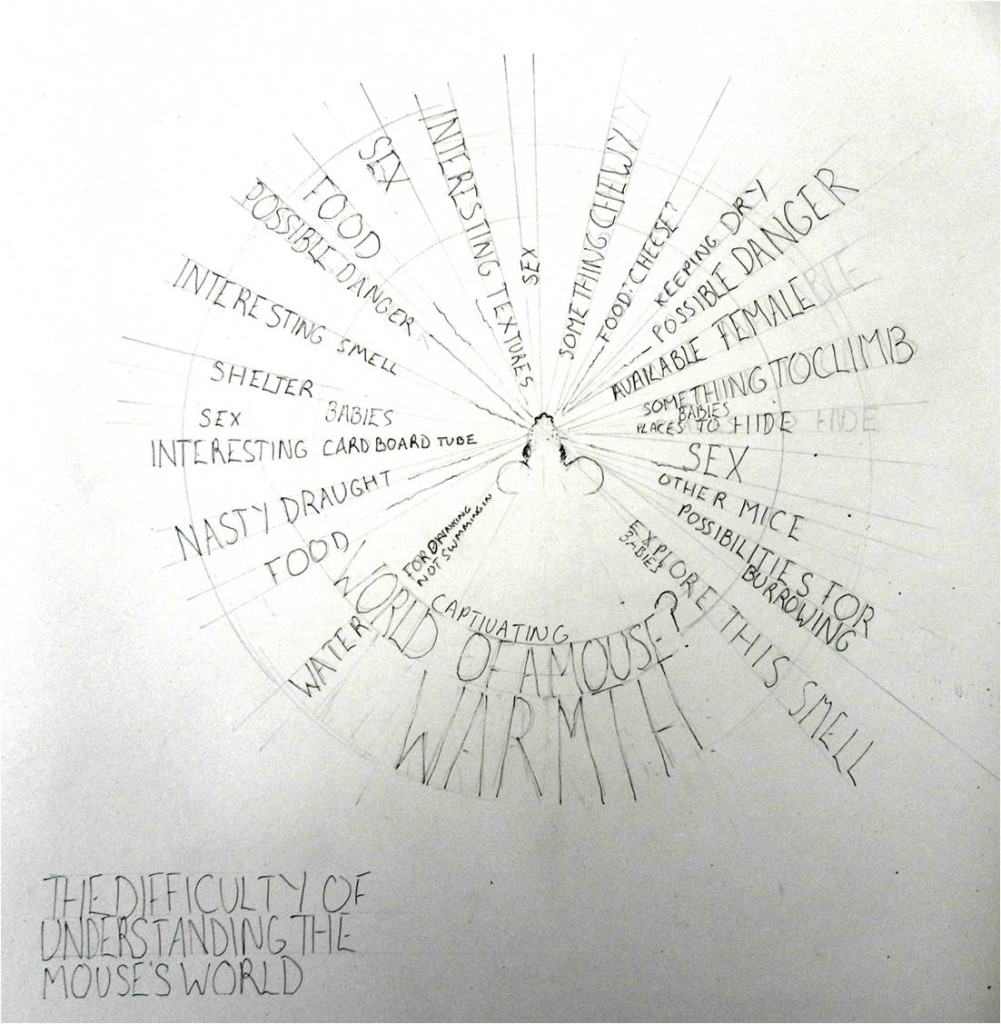

This sketch is an initial attempt to imagine the environment from the perspective of the animal itself.

Creating the comic strip

The visual contents of the MiceSpace website have emerged through a variety of approaches, for example diagramming, drawing, collage, projection. Among these is the below attempt at a comic strip or ‘graphic story telling’.

Helen writes: I have found much to be intrigued by in the work of thoughtful creatives such as Posy Simmonds, Marjane Satrapi, Art Spiegelman and Robert Crumb. At their very best comic strips are a seductive and potent means of storytelling, simultaneously unfolding showings and tellings through time. I thought I had a story about a changing viewpoint, or an attempt to see from different places, which I thought it might be interesting to investigate in this way.

It started with a niggle. Before I ever thought of drawing a graphic strip, I’d made an attempt early in my collaboration with Gail to make a sketch for the MiceSpace site above, describing it as ’… an initial attempt to imagine the environment from the perspective of the animal itself.’ But that sketch fratched at me – it was just generated out of ‘information about’ mice which I’d received as a result of being told. So it was just an external production, and that was the niggle. In the end it drove me into the local woods, full of animals, including mice, to try and understand in a different way about what it might mean actually to be one of them. That was the first stage in the making of the comic strip.

I tried to make a short video of myself trying to understand what it is to be a mouse by attempting to perform various mouse-like actions, picking up a nut, thinking about having – and not having – whiskers, having paws not hands, escaping a predator. As it turned out, this had the only possible effect it could have: of deepening my understanding of the impossibility of understanding.

A further twist came later when Gail visited me in my studio. We were looking together at a drawing I’d made of an alert mouse and Gail said something like, the problem is, this is just a picture of a mouse. Then she had to leave the studio to make a phone call and in a trice my mind somehow somersaulted me into banging a large piece of paper up on the wall and frantically scribbling, as if from a mouse-eye view, the inside of a lab cage with bars and nesting materials and scent-trails, so that when she came back we were both in a charcoaly, smudgy, very crudely suggested mouse world. Later on I tried more to imagine and think and feel in that way, and in doing so produced the final sequences for the comic strip as it is now.

So the comic strip came about over several years, and as a result of some crucial conversations with Gail. It certainly would never have existed without her input. The story it tries to tell is one of a transformational instant in the act of perception: from information about another being, to imagination of what it would be like to actually exist as that other being – despite the recognition of how ultimately impossible that imagining is. In so far as it addresses that crucial mind-flip, for me the comic strip attempts to do some real work.